Page 36 - PDF_Flip_Book

P. 36

Rod Machado’s Private/Commercial Pilot Handbook

12-34

Fig. 58

Fig. 57

When birds and other airplanes are flying in the

opposite direction, this should cause you concern.

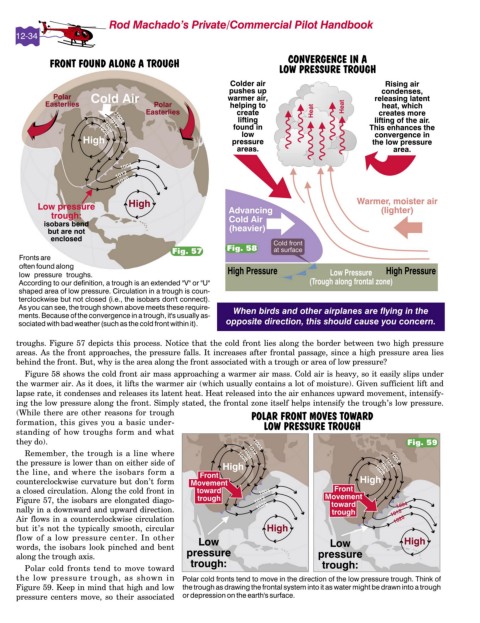

troughs. Figure 57 depicts this process. Notice that the cold front lies along the border between two high pressure

areas. As the front approaches, the pressure falls. It increases after frontal passage, since a high pressure area lies

behind the front. But, why is the area along the front associated with a trough or area of low pressure?

Figure 58 shows the cold front air mass approaching a warmer air mass. Cold air is heavy, so it easily slips under

the warmer air. As it does, it lifts the warmer air (which usually contains a lot of moisture). Given sufficient lift and

lapse rate, it condenses and releases its latent heat. Heat released into the air enhances upward movement, intensify-

ing the low pressure along the front. Simply stated, the frontal zone itself helps intensify the trough’s low pressure.

(While there are other reasons for trough

formation, this gives you a basic under-

standing of how troughs form and what

they do). Fig. 59

Remember, the trough is a line where

the pressure is lower than on either side of

the line, and where the isobars form a

counterclockwise curvature but don’t form

a closed circulation. Along the cold front in

Figure 57, the isobars are elongated diago-

nally in a downward and upward direction.

Air flows in a counterclockwise circulation

but it’s not the typically smooth, circular

flow of a low pressure center. In other

words, the isobars look pinched and bent

along the trough axis.

Polar cold fronts tend to move toward

the low pressure trough, as shown in

Figure 59. Keep in mind that high and low

pressure centers move, so their associated