Page 37 - PDF_Flip_Book

P. 37

Chapter 12 - Understanding Weather

12-35

tinuous. When in an airplane, temperature is the most

easily recognized discontinuity across a front.

Pilots flying across a front are likely to notice a sharper

temperature change at lower altitudes than higher ones

where air tends to become more homogenous. Since rela-

tive humidity varies with the moisture content of the air,

as well as the temperature of the air, you should also

expect changes in dew point with frontal passage. (My

grandpa always got upset after cold frontal passage when

we left the house door open. He’d yell, “Hey, I’m not pay-

ing to heat the neighborhood.” You can probably tell that

he desperately needed a course in thermodynamics!)

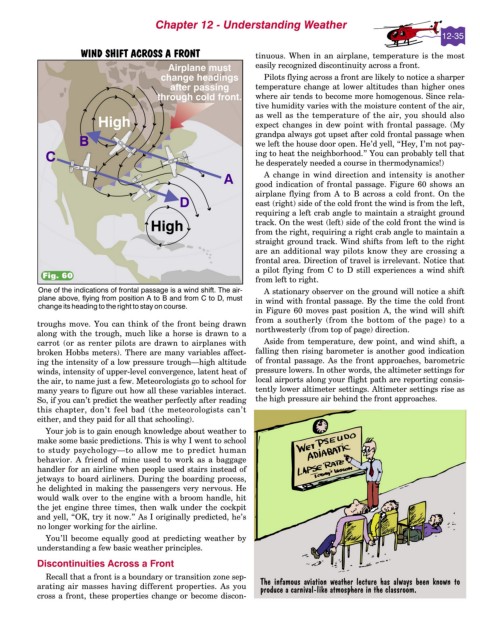

A change in wind direction and intensity is another

good indication of frontal passage. Figure 60 shows an

airplane flying from A to B across a cold front. On the

east (right) side of the cold front the wind is from the left,

requiring a left crab angle to maintain a straight ground

track. On the west (left) side of the cold front the wind is

from the right, requiring a right crab angle to maintain a

straight ground track. Wind shifts from left to the right

are an additional way pilots know they are crossing a

frontal area. Direction of travel is irrelevant. Notice that

a pilot flying from C to D still experiences a wind shift

Fig. 60

from left to right.

A stationary observer on the ground will notice a shift

in wind with frontal passage. By the time the cold front

in Figure 60 moves past position A, the wind will shift

from a southerly (from the bottom of the page) to a

troughs move. You can think of the front being drawn

northwesterly (from top of page) direction.

along with the trough, much like a horse is drawn to a

carrot (or as renter pilots are drawn to airplanes with Aside from temperature, dew point, and wind shift, a

broken Hobbs meters). There are many variables affect- falling then rising barometer is another good indication

ing the intensity of a low pressure trough—high altitude of frontal passage. As the front approaches, barometric

winds, intensity of upper-level convergence, latent heat of pressure lowers. In other words, the altimeter settings for

the air, to name just a few. Meteorologists go to school for local airports along your flight path are reporting consis-

many years to figure out how all these variables interact. tently lower altimeter settings. Altimeter settings rise as

So, if you can’t predict the weather perfectly after reading the high pressure air behind the front approaches.

this chapter, don’t feel bad (the meteorologists can’t

either, and they paid for all that schooling).

Your job is to gain enough knowledge about weather to

make some basic predictions. This is why I went to school

to study psychology—to allow me to predict human

behavior. A friend of mine used to work as a baggage

handler for an airline when people used stairs instead of

jetways to board airliners. During the boarding process,

he delighted in making the passengers very nervous. He

would walk over to the engine with a broom handle, hit

the jet engine three times, then walk under the cockpit

and yell, “OK, try it now.” As I originally predicted, he’s

no longer working for the airline.

You’ll become equally good at predicting weather by

understanding a few basic weather principles.

Discontinuities Across a Front

Recall that a front is a boundary or transition zone sep-

arating air masses having different properties. As you The infamous aviation weather lecture has always been known to

produce a carnival-like atmosphere in the classroom.

cross a front, these properties change or become discon-