Page 28 - PDF_Flip_Book

P. 28

Chapter 9 - Airspace: The Wild Blue, Green & Red Yonder 9-31

A friend of mine was departing Ontario airport, in the Los

Angeles area, when Ontario had a TRSA. He was heading 270° (west), toward the

Pacific Ocean, and wanted to go to San Diego (south, to his left about 90°). He

kept asking for a heading toward San Diego. but the controller couldn’t comply

because of a traffic conflict. Finally, in frustration, my friend said, “Ontario

Approach, this is 2132 Bravo, I’ve been flying 270 for 10 minutes, can’t I please

have a more southerly heading?” The controller replied, “All right 32 Bravo, turn

left to a heading of 269!” See what I mean? It gets busy sometimes.

be talking to approach control (when approaching) or ground control and don’t want TRSA service, you should state,

“Negative TRSA service.” There may be times when you want to fly your own (and perhaps more expeditious) route

to the airport and have ATC provide only traffic information for you. At times like these, when it’s real busy, TRSA

service can entail extensive delay vectoring. In this instance you might say:

“Binghamton Approach, this is 2132 Bravo, negative TRSA service, request traffic advisories enroute to

Binghamton airport, over.”

When approaching and before entering Binghamton’s Class D airspace, you’d cancel traffic advisories with

approach control, then establish communication with Binghamton Tower and request landing instructions.

Conversely, when departing an airport, you can state, “Negative TRSA service” to the ground controller. This tells

the controller that you want to fly your own route out of the airport.

You might be wondering why we have TRSAs when we have Class B and C airspace that seem to serve a similar

function. TRSAs belong to airports that don’t qualify for Class B or C airspace, yet have enough traffic to justify the

presence of some sort of radar service.

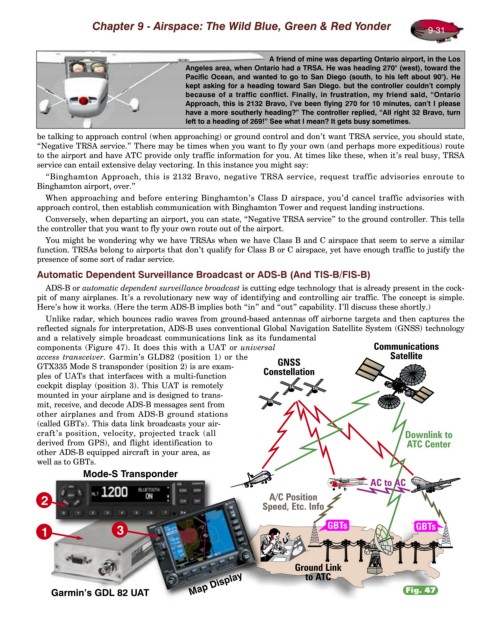

Automatic Dependent Surveillance Broadcast or ADS-B (And TIS-B/FIS-B)

ADS-B or automatic dependent surveillance broadcast is cutting edge technology that is already present in the cock-

pit of many airplanes. It’s a revolutionary new way of identifying and controlling air traffic. The concept is simple.

Here’s how it works. (Here the term ADS-B implies both “in” and “out” capability. I’ll discuss these shortly.)

Unlike radar, which bounces radio waves from ground-based antennas off airborne targets and then captures the

reflected signals for interpretation, ADS-B uses conventional Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) technology

and a relatively simple broadcast communications link as its fundamental

components (Figure 47). It does this with a UAT or universal

access transceiver. Garmin’s GLD82 (position 1) or the

GTX335 Mode S transponder (position 2) is are exam-

ples of UATs that interfaces with a multi-function

cockpit display (position 3). This UAT is remotely

mounted in your airplane and is designed to trans-

mit, receive, and decode ADS-B messages sent from

other airplanes and from ADS-B ground stations

(called GBTs). This data link broadcasts your air-

craft’s position, velocity, projected track (all

derived from GPS), and flight identification to

other ADS-B equipped aircraft in your area, as

well as to GBTs.

Mode-S Transponder

2

1 3

Map Display

Garmin’s GDL 82 UAT Fig. 47