Page 4 - PDF_Flip_Book

P. 4

Rod Machado’s Private/Commercial Pilot Handbook

2-24

Parasite Drag

The following three types of drag fall under the catego-

ry of parasite drag.

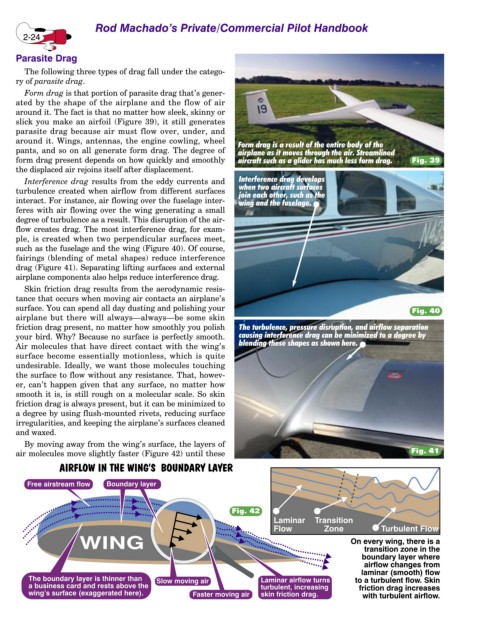

Form drag is that portion of parasite drag that’s gener-

ated by the shape of the airplane and the flow of air

around it. The fact is that no matter how sleek, skinny or

slick you make an airfoil (Figure 39), it still generates

parasite drag because air must flow over, under, and

around it. Wings, antennas, the engine cowling, wheel Form drag is a result of the entire body of the

pants, and so on all generate form drag. The degree of airplane as it moves through the air. Streamlined

form drag present depends on how quickly and smoothly aircraft such as a glider has much less form drag. Fig. 39

the displaced air rejoins itself after displacement.

Interference drag results from the eddy currents and Interference drag develops

turbulence created when airflow from different surfaces when two aircraft surfaces

join each other, such as the

interact. For instance, air flowing over the fuselage inter- wing and the fuselage.

feres with air flowing over the wing generating a small

degree of turbulence as a result. This disruption of the air-

flow creates drag. The most interference drag, for exam-

ple, is created when two perpendicular surfaces meet,

such as the fuselage and the wing (Figure 40). Of course,

fairings (blending of metal shapes) reduce interference

drag (Figure 41). Separating lifting surfaces and external

airplane components also helps reduce interference drag.

Skin friction drag results from the aerodynamic resis-

tance that occurs when moving air contacts an airplane’s

surface. You can spend all day dusting and polishing your

Fig. 40

airplane but there will always—always—be some skin

friction drag present, no matter how smoothly you polish The turbulence, pressure disruption, and airflow separation

your bird. Why? Because no surface is perfectly smooth. causing interference drag can be minimized to a degree by

blending these shapes as shown here.

Air molecules that have direct contact with the wing’s

surface become essentially motionless, which is quite

undesirable. Ideally, we want those molecules touching

the surface to flow without any resistance. That, howev-

er, can’t happen given that any surface, no matter how

smooth it is, is still rough on a molecular scale. So skin

friction drag is always present, but it can be minimized to

a degree by using flush-mounted rivets, reducing surface

irregularities, and keeping the airplane’s surfaces cleaned

and waxed.

By moving away from the wing’s surface, the layers of

air molecules move slightly faster (Figure 42) until these Fig. 41

Fig. 42