Page 10 - PDF_Flip_Book

P. 10

Chapter 3 - Engines: Knowledge of Engines Is Power

3-27

During a descent, your job is to maintain stable

cylinder head temperatures (CHT) and oil temper-

atures (i.e., keep their temperature indications in

the green). On some airplanes, gear extension or

even partial flap extension at high speeds can be

used in lieu of large power reductions to start a

descent (check your POH). While momentary power

reductions aren’t as harmful if the power is

immediately restored, large ones over long

periods can be damaging. Try planning your

descents so engine temperatures change

slowly from their previous cruise values.

The Propeller

Propellers come in all sizes and colors, but they

are of two basic types: fixed pitch and constant

speed. In an airplane with a fixed pitch prop, one

lever—the throttle—controls both power and pro-

Fig. 46

peller blade RPM (revolutions per minute). In a

constant speed prop, there are separate con-

trols for power and RPM.

When you start your flight training, you’ll

probably fly an airplane with a fixed pitch

propeller. Fixed pitch propellers have their

pitch (angle of attack) fixed during the forg-

ing process. The angle is set in stone (actu-

ally, aluminum). This pitch can’t be changed

except by replacing the propeller, which pret-

ty much prevents you from changing the pro-

peller’s pitch in flight. Fixed pitch props are not

ideal for any one thing, yet they’re in many ways

best for everything. They represent a compromise

between the best

angle of attack for climb and the best angle for cruise. They are simple to oper-

ate, and easier (thus less expensive) to maintain.

On fixed pitch propeller airplanes, engine power and engine RPM are both con-

trolled by the throttle. One lever does it all, power equals RPM, and that’s the end.

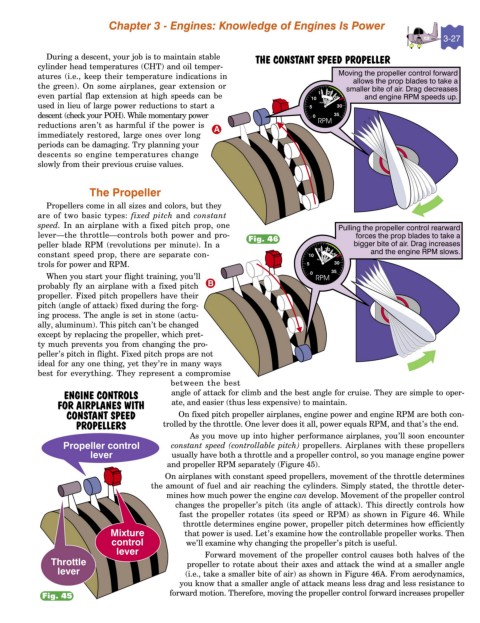

As you move up into higher performance airplanes, you’ll soon encounter

constant speed (controllable pitch) propellers. Airplanes with these propellers

usually have both a throttle and a propeller control, so you manage engine power

and propeller RPM separately (Figure 45).

On airplanes with constant speed propellers, movement of the throttle determines

the amount of fuel and air reaching the cylinders. Simply stated, the throttle deter-

mines how much power the engine can develop. Movement of the propeller control

changes the propeller’s pitch (its angle of attack). This directly controls how

fast the propeller rotates (its speed or RPM) as shown in Figure 46. While

throttle determines engine power, propeller pitch determines how efficiently

that power is used. Let’s examine how the controllable propeller works. Then

we’ll examine why changing the propeller’s pitch is useful.

Forward movement of the propeller control causes both halves of the

propeller to rotate about their axes and attack the wind at a smaller angle

(i.e., take a smaller bite of air) as shown in Figure 46A. From aerodynamics,

you know that a smaller angle of attack means less drag and less resistance to

Fig. 45 forward motion. Therefore, moving the propeller control forward increases propeller